Hahn-Banach Extension Theorem

Theorem1

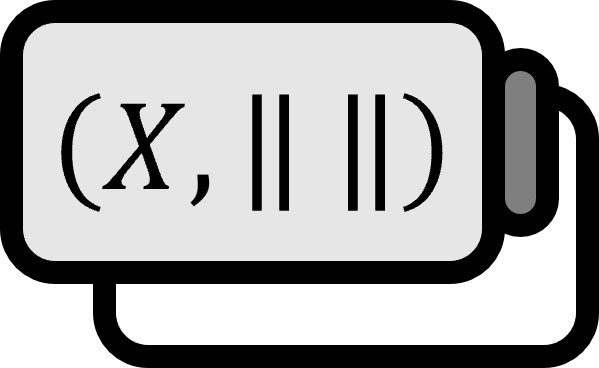

Let’s call $(X, \left\| \cdot \right\|)$ a normed space. Let $Y \subset X$. Also, given a linear functional $y^{\ast} \in Y^{\ast}$ of $Y$. Then there exists a linear functional $x^{\ast} \in X^{\ast}$ of $X$ that satisfies the following equation.

$$ \begin{equation} x^{\ast}(y)=y^{\ast}(y),\quad \forall y \in Y \end{equation} $$

$$ \begin{equation} \| x^{\ast}\|_{X^{\ast}} = \| y^{\ast}\|_{Y^{\ast}} \end{equation} $$

Explanation

In simple terms, this means that the dual of a subspace can be extended to the dual of the entire space. In other words, all linear functionals of the subspace have a counterpart in the entire space’s linear functionals with the same function values and norms. Also, let’s treat the norm space $X$ as a $\mathbb{ C}$-vector space.

Auxiliary Theorem: Hahn-Banach Theorem for Semi Norms

Let $X$ be a $\mathbb{C}$-vector space and $Y \subset X$. Let’s call $p : X \to \mathbb{ R}$ a seminorm of $X$. And suppose that $ y^{\ast} : Y \to \mathbb{ C}$ is a linear functional of $Y$ that satisfies the following condition.

$$ | y^{\ast}(y) | \le p(y),\quad \forall y\in Y $$

Then there exists a linear functional $x^{\ast} : X \to \mathbb{C}$ of $X$ that satisfies the following conditions.

$$ x^{\ast}(y)=y^{\ast}(y),\quad \forall y \in Y $$

$$ | x^{\ast}(x) | \le p(x),\quad \forall x \in X $$

Proof

Let’s denote the norms of $X$ and $Y$ as $\left\| \cdot \right\|$, the norms of $X^{\ast}$ and $Y^{\ast}$ as $\left\| \cdot \right\|_{X^{\ast}}$ and $\left\| \cdot \right\|_{Y^{\ast}}$ respectively. Let’s assume $p : X \to \mathbb{R}$ is defined as follows.

$$ p(x)=\|y^{\ast}\|_{Y^{\ast}} \|x \|_{X},\quad x\in X $$

Then $p$ can be shown to be quasi-linear. By definition, since $0 \le p$, $p$ is a seminorm. Also, the following equation holds:

$$ \begin{align*} y^{\ast}(y) \le & | y^{\ast}(y) | \\ =&\ \left| \|y\| \frac{1}{\| y\|} y^{\ast}(y) \right| \\ =&\ \|y\| \left| y^{\ast}\left( \frac{y}{\|y\|} \right) \right| \\ \le & \|y\| \left\|y^{\ast}\right\|_{Y^{\ast}} \\ =&\ p(y) \end{align*} $$

In the third line, since $\|y\|$ is a constant, it can come out of the absolute value, and since $y^{\ast}$ is linear, $\frac{1}{\|y\|}$ entered into the function. Moreover, the fourth line is $\left\| \frac{y}{\|y\|} \right\| =1$ and by the definition of dual norm, since $\| y^{\ast}\|_{Y^{\ast}}=\sup \limits_{\substack{ \|y\| \le 1 \\ y\in Y}} |y^{\ast}(y)|$, it holds. Therefore, the conditions for using the auxiliary theorem are satisfied, thus there exists a linear functional $X$ $x^{\ast} : X \to \mathbb{ C}$ that satisfies the following conditions.

$$ x^{\ast}(y)=y^{\ast}(y), \quad \forall y \in Y $$

$$ \begin{equation} | x^{\ast}(x) | \le p(x),\quad \forall x \in X \end{equation} $$

The first condition is equivalent to $(1)$. By $(3)$,

$$ |x^{\ast}(x)| \le p(x) =\|y^{\ast}\|_{Y^{\ast}} \|x\| $$

By the definition of the dual norm,

$$ \|x^{\ast}\|_{X^{\ast}} = \sup \limits_{\substack{ \|x\| \le 1 \\ x\in X}}\|y^{\ast}\|_{Y^{\ast}} \|x\| = \|y^{\ast}\|_{Y^{\ast}} $$

Thus, it satisfies the conditions of $(2)$.

■

Corollaries

1

If $X$ is a norm space and $x_{0} \in X$, then there exists a linear functional $x^{\ast} \in X^{\ast}$ satisfying the following condition.

$$ \|x^{\ast}\|_{X^{\ast}} = 1,\quad x^{\ast}(x_{0}) = \| x_{0}\| $$

Proof

Let’s say $Y=\left\{ \lambda | \lambda x_{0} \in \mathbb{ R}\right\}$. Then $Y$ becomes a subspace of $X$. Now, let’s define a linear functional $y^{\ast} : Y \to \mathbb{R}$ of $Y$ as follows.

$$ y^{\ast}(y)=y^{\ast} (\lambda x_{0}):=\lambda \|x_{0}\|,\quad y=\lambda x_{0}\in Y $$

It is easy to verify that $y^{\ast}$ is indeed linear, so we omit this. By the definition of $y^{\ast}$,

$$ | y^{\ast}(y) |=\lambda\|x_{0} \|=\|\lambda x_{0}\|=\| y\| $$

By the definition of dual norm, since $\| y^{\ast}\|_{Y^{\ast}}=\sup \limits_{\substack{ \|y\| \le 1 \\ y\in Y}} |y^{\ast}(y)|$,

$$ \begin{equation} \|y^{\ast}\|_{Y^{\ast}} = 1 \end{equation} $$ Additionally,

$$ y^{\ast}(x_{0})=\|x_{0}\| \tag{5} $$

By the Hahn-Banach extension theorem, given $y^{\ast}$, there exists a linear functional $x^{\ast}$ of $X$ such that $\|x^{\ast}\|_{X^{\ast}} = 1 = \|y^{\ast}\|_{Y^{\ast}}$ and satisfies $x^{\ast}(y)=y^{\ast}(y),\forall y \in Y$. Then by $(4)$ and $(5)$,

$$ \|x^{\ast}\|_{X^{\ast}} = \|y^{\ast}\|_{Y^{\ast}} = 1 $$

$$ x^{\ast}(x_{0})=y^{\ast}(x_{0})=\| x_{0}\| $$

■

2

Let’s say $X$ is a $\mathbb{C}$-vector space and both $Y \subset S$ are subspaces of $X$. If $s \in S$ equals $d (s, Y) = \delta > 0$, then there exists a linear functional $x^{\ast} \in X^{\ast}$ satisfying the following.

$$ \left\| x^{\ast} \right\|_{X^{\ast}} \le 1 $$

$$ \begin{align*} y^{\ast} (s) =&\ y^{\ast} (s) = \delta, \quad s \in (S \setminus Y) \\ x^{\ast} (y) =&\ y^{\ast} (y) = 0, \quad y \in Y \end{align*} $$

$d \left( s, Y \right)$ represents the shortest distance between the point $s$ and the set $Y$, namely $d (s,Y) := \inf \limits_{y \in Y} \left\| s-y \right\|$.

Proof2

If we say,

$$ S := Y + \mathbb{C} s = \left\{ y + \lambda s : y \in Y , \lambda \in \mathbb{C} \right\} $$

then $S \subset X$. Defining the function $y^{\ast} : S \to \mathbb{C}$ as

$$ y^{\ast} \left( y + \lambda s \right) := \lambda \delta $$

naturally grants $y^{\ast}$ linearity. Now, to confirm that $y^{\ast}$ is a function, let’s assume $y_{1} + \lambda_{1} s = y_{2} + \lambda_{2} s$ and suppose $\lambda_{1} \ne \lambda_{2}$, then since $y_{1} - y_{2} = \left( \lambda_{2} - \lambda_{2} \right) s$, it leads to $\displaystyle s = {{ 1 } \over { \lambda_{2} - \lambda_{1} }} \left( y_{1} - y_{2} \right)$, and since $Y$ is a vector space, it must be closed under addition, thus it must be $s \in Y$. However, this contradicts $d (s, Y) > 0$, therefore it must be $\lambda_{1} = \lambda_{2}$,

$$ y^{\ast} \left( y_{1} + \lambda_{1} s \right) = \lambda_{1} \delta = \lambda_{2} \delta = y^{\ast} \left( y_{2} + \lambda_{1} s \right) $$

thus, $y^{\ast}$ is well-defined as a function. For all $y + \lambda s \in S$,

$$ \begin{align*} \left| y^{\ast} (y + \lambda s) \right| =&\ \left| \lambda \delta \right| \\ =&\ \left| \lambda \right| d (s,Y) \\ =&\ \left| \lambda \right| \inf_{y \in Y} \left\| s-y \right\| \\ =&\ \left\| s- \lambda y \right\| \\ \le& \left\| y + \lambda s \right\| \end{align*} $$ therefore, $y^{\ast}$ is bounded, and especially $\left\| y^{\ast} \right\| \le 1 $. Since $y^{\ast} : S \to \mathbb{C}$ is a bounded linear function, and by the Hahn-Banach theorem, for all $s \in S$ there exists a linear functional $x^{\ast} \in X^{\ast}$ that satisfies $x^{\ast}(s) = y^{\ast}(s)$. Meanwhile, by substituting $\lambda = 0$ in the definition of $y^{\ast}$, since $y^{\ast} (y + 0 s) = 0 $, for all $y \in Y$,

$$ y^{\ast} (y ) = x^{\ast}(y) = 0 $$

Additionally, since $y^{\ast}$ is linear,

$$ y^{\ast} (s) = y^{\ast} (y) + 1 y^{\ast} (s)= y^{\ast} (y + 1s) = 1 \delta $$

In other words, for $s \in (S \setminus Y)$,

$$ y^{\ast} (s) = x^{\ast}(s) = \delta $$

■

Appendix

Appendix1

Let’s say $x_{1},x_{2} \in X$ and $\lambda \in \mathbb{C}$. Then,

$$ \begin{align*} p(x_{1} + x_{2}) =&\ \|y^{\ast}\|_{Y^{\ast}} \|x_{1} + x_{2} \| \\ \le & \|y^{\ast}\|_{Y^{\ast}} \big(\| x_{1}\| +\|x_{2}\| \big) \\ =&\ \|y^{\ast}\|_{Y^{\ast}} \|x_{1}\| + \|y^{\ast}\|_{Y^{\ast}} \|x_{2}\| \\ =&\ p(x_{1})+p(x_{2}) \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} p(\lambda x_{1}) =&\ \|y^{\ast}\|_{Y^{\ast}} \|\lambda x_{1} \| \\ =&\ |\lambda | \|y^{\ast}\|_{Y^{\ast}} \|x_{1}\| \\ =&\ | \lambda| p(x_{1}) \end{align*} $$

thus, $p$ is quasi-linear.

■

Appendix2

Since $X$ is a vector space, a scalar multiplied by an element of $X$ is also an element of $X$. Therefore, $Y$ becomes a subset of $X$. To show that the subset $Y$ is a subspace, it must be shown to be closed under addition and scalar multiplication. Let’s say $y_{1}=\lambda_{1}x_{0} \in Y$, $ y_{2}=\lambda_2x_{0} \in Y$, and $\lambda_{1}, \lambda_2, k \in \mathbb{R}$; and $\lambda_{1}+\lambda_2=\lambda_{3}\in \mathbb{R}$, $k\lambda_{1}=\lambda_{4}\in \mathbb{ R}$. Then,

$$ y_{1}+y_{2}=\lambda_{1} x_{0} + \lambda_2 x_{0}=\lambda_{3}x_{0}\in Y $$

$$ ky_{1}=k(\lambda_{1}x_{0})=(k \lambda_{1})x_{0}=\lambda_{4} x_{0} \in Y $$

Therefore, $Y$ is a subspace of $X$.

■

Robert A. Adams and John J. F. Foutnier, Sobolev Space (2nd Edition, 2003), p6 ↩︎

http://mathonline.wikidot.com/corollaries-to-the-hahn-banach-theorem ↩︎