Lefschetz Fixed Point Theorem Proof

Theorem 1

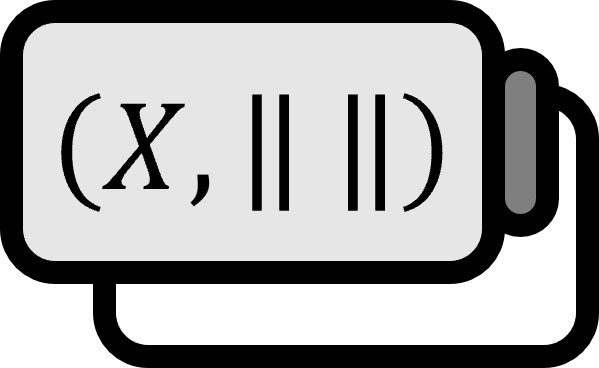

Let’s denote the scalar field of norm space $(X , \left\| \cdot \right\|)$ as $\mathbb{C}$. Then

Explanation

$\overline{ B ( 0 ; 1 ) } := \left\{ x \in X : \| x \| \le 1 \right\}$ denotes the closed unit ball. According to the Riesz’s theorem, to determine whether the entire space is finite-dimensional, it is enough to check a very small region. It is often not considered necessary and sufficient conditions for finite-dimensional normed spaces, which makes this theorem very mathematical.

Proof

Strategy: A simple homeomorphism from the manageable $\mathbb{C}^{n}$ to $X$ is given, transferring the compactness from $\mathbb{C}^{n}$ to $X$. In reverse, based on the compactness of $\overline{ B ( 0 ; 1 ) }$, a finite-dimensional vector space is created, and it is shown that it actually includes $X$.

$(\implies)$

If we consider $\dim X = n$, there exists a basis $\left\{ e_{1} , \cdots , e_{n} \right\}$ for $X$. If we define the function $f : ( \mathbb{C}^{n} , \| \cdot \|_{1} ) \to (X , \| \cdot \| )$ as $f(\lambda_{1} , \cdots , \lambda_{n} ) : = \lambda_{1} e_{1} + \cdots + \lambda_{n} e_{n}$, $f$ is a continuous bijection.

The closed unit ball $\overline{ B_{ \| \cdot \|_{1} } ( 0 ; 1 ) } = \left\{ (\lambda_{1} , \cdots , \lambda_{n}) \in \mathbb{C}^{n} \ | \ | \lambda_{1} | + \cdots + | \lambda_{n} | \le 1 \right\}$ in $\mathbb{C}^{n}$ is compact by the Heine-Borel theorem. Since $f$ is continuous, $f \left( \overline{ B_{ \| \cdot \|_{1} } ( 0 ; 1 ) } \right)$ is also compact.

Meanwhile, since $\| \lambda_{1} e_{1} + \cdots + \lambda_{n} e_{n} \| \le | \lambda_{1} | + \cdots + | \lambda_{n} |$, it follows $\overline{ B ( 0 ; 1 ) } \subset f \left( \overline{ B_{ \| \cdot \|_{1} } ( 0 ; 1 ) } \right)$. Since $\overline{ B ( 0 ; 1 ) }$ is a closed subset of the compact set $f \left( \overline{ B_{ \| \cdot \|_{1} } ( 0 ; 1 ) } \right)$, it is compact.

$(\impliedby)$

Let’s consider $0 < \varepsilon < 1$.

Since $\overline{ B ( 0 ; 1 ) }$ is compact, there exists a finite subcover that satisfies $\displaystyle \overline{ B ( 0 ; 1 ) } \subset \bigcup_{i=1}^{m} B \left( x_{i} ; \varepsilon \right)$ for the open cover $\displaystyle \bigcup_{x \in \overline{ B ( 0 ; 1 ) } } { B \left( x ; \varepsilon \right) }$. Let’s say $M := \text{span} \left\{ x_{1} , \cdots , x_{n} \right\}$.

$\displaystyle \overline{ B ( 0 ; 1 ) } \subset \bigcup_{i=1}^{m} B \left( x_{i} ; \varepsilon \right)$ means that $\displaystyle \overline{ B ( 0 ; 1 ) } \subset \bigcup_{ m \in M } B \left( m ; \varepsilon \right)$ holds. Since $ m \in \text{span} \left\{ x_{1} , \cdots , x_{n} \right\}$ from the beginning, no matter how small the diameter $\varepsilon$ is chosen, this inclusion relation continues to hold. Therefore, for $k \in \mathbb{N}$

$$ \overline{ B ( 0 ; 1 ) } \subset \bigcup_{ m \in M } B \left( m ; \varepsilon \right) \subset \bigcup_{ m \in M } B \left( m ; \varepsilon^2 \right) \subset \cdots \subset \bigcup_{ m \in M } B \left( m ; \varepsilon^k \right) $$

Now, considering any non-zero vector $x \in X$, for some $y_{k} \in M$, $\displaystyle z_{k} : = B ( 0 ; \varepsilon^k )$

$$ {{ x } \over { \| x \| }} = y_{k} + z_{k} $$

When $k \to \infty$, since $z_{k} \to 0$

$$ y_{k} = {{ x } \over { \| x \| }} - z_{k} \to {{ x } \over { \| x \| }} \in \overline{ M } = M $$

That is, since $x \in M$, and $X \subset M$, but since $M \subset X$

$$ X = \text{span} \left\{ x_{1} , \cdots , x_{n} \right\} $$

Therefore, $X$ is a finite-dimensional vector space.

■

See Also

Generalization from Euclidean Spaces

Riesz’s theorem points out the compactness of the closed unit ball $\overline{B (0;1)}$ in norm spaces as an equivalent condition of finiteness of dimensions. Since the $k$-cell $[0,1]^{k}$ is compact in Euclidean spaces, and there exists a homeomorphism with the closed unit ball, Riesz’s theorem can be seen as a generalization concerning the compactness of the $k$-cell.

Kreyszig. (1989). Introductory Functional Analysis with Applications: p80. ↩︎