Properties of Linear Operators

Theorem 1

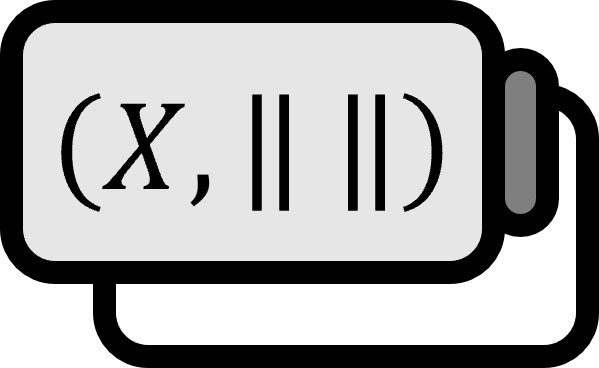

$T : (X , \left\| \cdot \right\|_{X}) \to ( Y , \left\| \cdot \right\|_{Y} )$ is called a linear operator.

(a) If $T$ is bounded, for all $x \in X$, $\left\| T(x) \right\|_{Y} \le \left\| T \right\| \left\| x \right\|_{X}$

(b) $T$ is continuous $\iff$ $T$ is bounded

(c) If $X$ is a finite-dimensional space, then $T$ is continuous.

(d) If $Y$ is a Banach space, then $( B(X,Y) , \| \cdot \| )$ is a Banach space.

Explanation

$B(X,Y)$ is the space of bounded linear operators, so by (b), it is known that all operators in this space are continuous. Being linear is useful, but if it is not only continuous but also complete, it is definitely a very good space.

(a) is widely used, and if there are no major problems, it is usually just written as $\| Tx \| \le \| T \| \| x \| $.

(d) In norm $\| \cdot \|$ is the operator norm.

Proof

(a)

Strategy: Use the fact that $\| x \|_{X}$ is a scalar to go in and out of $T$.

Since $T$ is bounded, there exists some $c> 0$ such that

$$ {{ \| T(x) \|_{Y} } \over { \| x \|_{X} }} \le c $$

Since $\| x \|_{X}$ is a scalar and $T$ is linear,

$$ {{ \| T(x) \|_{Y} } \over { \| x \|_{X} }} =\left\| {{1} \over {\| x \|_{X} }} T \left( x \right) \right\|_{Y} = \left\| T \left( {{x} \over {\| x \|_{X} }} \right) \right\|_{Y} $$

From the definition of operator norm, since $\left\| T \right\| = \sup \limits_{\substack{x\in X \\ \left\| x \right\|=1 }} \left\| T(x) \right\|_{Y}$,

$$ {{ \| T(x) \|_{Y} } \over { \| x \|_{X} }} = \left\| T \left( {{x} \over {\| x \|_{X} }} \right) \right\|_{Y} \le \sup \limits_{\substack{x\in X \\ \left\| x \right\|=1 }} \left\| T(x) \right\|_{Y} = \| T \| $$

Multiplying both sides by the scalar $\| x \|_{X}$ gives

$$ \| T(x) \|_{Y} \le \| T \| \| x \|_{X} $$

■

(b)

Strategy: Direct deduction using epsilon-delta argument. $(\implies)$ employs reductio ad absurdum, and according to continuity, it constructs a sequence that would be a contradiction to the assumption.

$(\impliedby)$

If $T = 0$, it’s naturally continuous, so consider the case when $T \ne 0$. For any $x_{0} \in X$, let’s say $\| x - x_{0} \| < \delta$.

Since $T$ is a bounded linear operator, by (a)

$$ \| Tx - Tx_{0} \| = \| T ( x - x_{0} ) \| \le \| T \| \| x - x_{0} \| < \| T \| \delta $$

For any $\varepsilon > 0$, if we set $\displaystyle \delta = {{ \varepsilon } \over { \| T \| }}$, then $\| Tx - Tx_{0} \| < \varepsilon$, so $T$ is continuous.

$(\implies)$

If we assume that $\| T \| = \infty$,

$$ \| x_{n} \| = 1 $$

$$ \lim_{n \to \infty} \| T x_{n} \| = \infty $$

There exists a sequence of $X$, $\left\{ x_{n} \right\}_{ n \in \mathbb{N} }$, such that defining $\displaystyle z_{n} := {{x_{n}} \over { \sqrt{ \| Tx_{n} \| } }}$,

$$ \lim_{n \to \infty} z_{n} = 0 $$

Since $T$ is continuous,

$$ 0 = \lim_{n \to \infty} \| T( 0 ) \| = \left\| T \left( \lim_{n \to \infty} z_{n} \right) \right\| = \lim_{n \to \infty} \| T( z_{n} ) \| = \lim_{n \to \infty} \left\| T \left( {{x_{n}} \over { \sqrt{ \| Tx_{n} \| } }} \right) \right\|= \lim_{n \to \infty} \sqrt{ \| T(x_{n} ) \| } = \infty $$

This is a contradiction to the assumption, so $T$ is bounded.

■

(c)

Strategy: To show continuity according to (b), it is sufficient to demonstrate boundedness. Using the properties of finite-dimensional spaces, showing that $T$ is bounded is relatively straightforward.

If we say $\dim X = n$, then $X$ has a basis $\left\{ e_{1} , \cdots , e_{n} \right\}$ and any $x \in X$ for $t_{i} \in \mathbb{C}$ is

$$ x = \sum_{i=1}^{n} t_{i} e_{i} $$

Since $T$ is a linear operator,

$$ Tx = T \left( \sum_{i=1}^{n} t_{i} e_{i} \right) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} | t_{i} | T \left( e_{i} \right) $$

Taking the norm $\| \cdot \|_{Y}$ on both sides gives

$$ \begin{equation} \| Tx \|_{Y} = \left\| \sum_{i=1}^{n} t_{i} T \left( e_{i} \right) \right\|_{Y} \le \sum_{i=1}^{n} | t_{i} | \| T ( e_{i} ) \|_{Y} \le \max_{1 \le i \le n} \| T ( e_{i} ) \|_{Y} \sum_{i=1}^{n} | t_{ i} | \end{equation} $$

Now let’s define a new norm $\displaystyle \left\| \sum_{i=1}^{n} t_{i} e_{i} \right\|_{1} := \sum_{i=1}^{n} | t_{ i} |$. Since all norms defined in a finite-dimensional vector space are equivalent,

$$ C \left\| \sum_{i=1}^{n} t_{i} e_{i} \right\|_{1} \le \left\| \sum_{i=1}^{n} t_{i} e_{i} \right\|_{X} $$

There exists some $C>0$ that satisfies. Therefore,

$$ \sum_{i=1}^{n} | t_{ i} | = \left\| \sum_{i=1}^{n} t_{i} e_{i} \right\|_{1} \le {{1} \over {C}} \left\| \sum_{i=1}^{n} t_{i} e_{i} \right\|_{X} = {{1} \over {C}} \| x \|_{X} $$

Applying to $(1)$ gives

$$ \| T x \|_{Y} \le {{1} \over {C}} \max_{1 \le i \le n} \| T(e_{i} ) \|_{Y} \cdot \| x \|_{X} $$

Therefore, $\displaystyle \| T \| \le {{1} \over {C}} \max_{1 \le i \le n} \| T(e_{i} ) \|_{Y} < \infty$ but since $T$ is a bounded linear operator, by (b), it is continuous.

■

(d)

Strategy: Convert the discussion to $T(x) \in T(X) \subset Y$ by drawing out completeness in Banach space $Y$.

Part 1. For the normed space $( B(X,Y) , \| \cdot \| )$, $\| \cdot \|$ satisfies the following conditions for $T \in B(X,Y)$,

(i): $$ \| T \| = \sup\limits_{\substack{x\in X \\ \left\| x \right\|=1 }} \| T(x) \| \ge 0 $$

(ii): $$ \| T \| = \sup\limits_{\substack{x\in X \\ \left\| x \right\|=1 }} \| T(x) \| = 0 \iff T = 0 $$

(iii): $$ \| \lambda T \| = \sup\limits_{\substack{x\in X \\ \left\| x \right\|=1 }} \| \lambda T(x) \| =\sup\limits_{\substack{x\in X \\ \left\| x \right\|=1 }} \lambda \| T(x) \| = \lambda \sup\limits_{\substack{x\in X \\ \left\| x \right\|=1 }} \| T(x) \| $$

(iv): $$ \begin{align*} \| T_{1} + T_{2} \| =& \sup\limits_{\substack{x\in X \\ \left\| x \right\|=1 }} \| (T_{1} + T_{2})(x) \| \\ \le & \sup\limits_{\substack{x\in X \\ \left\| x \right\|=1 }} \left( \| T_{1} (x) \| + \| T_{2}(x) \| \right) \\ \le & \sup\limits_{\substack{x\in X \\ \left\| x \right\|=1 }} \| T_{1}(x) \| + \sup\limits_{\substack{x\in X \\ \left\| x \right\|=1 }} \| T_{2}(x) \| \end{align*} $$

Part 2. Completeness

Defining a Cauchy sequence of $B(X,Y)$, $\left\{ T_{n} \right\}_{n \in \mathbb{N}}$, for any $\varepsilon > 0$,

$$ \| T_{n} - T_{m} \| < \varepsilon $$

According to (a), for all $x \in X$,

$$ \| T_{n} x - T_{m} x \| = \| ( T_{n} - T_{m} ) x \| \le \| T_{n} - T_{m} \| \| x \| < \varepsilon \| x \| $$

Therefore, $\left\{ T_{n}x \right\}$ is a Cauchy sequence in $Y$. Since $Y$ is assumed to be complete, for some $Tx \in Y$

$$ \lim_{m \to \infty } T_{m}x = Tx $$

Again, according to (a), for all $x \in X$,

$$ \| T_{n} x - T x \| = \left\| T_{n} x - \lim_{m \to \infty} T_{m} x \right\| = \lim_{m \to \infty} \left\| T_{n} x - T_{m} x \right\| < \varepsilon \| x \| $$

For all $x \in X$, since $\displaystyle {{ \| ( T_{n} - T ) x \| } \over { \| x \| }} < \epsilon$,

$$ ( T_{n} - T ) \in B(X,Y) $$

Meanwhile, Part 1 showed that $B(X,Y)$ is a vector space,

$$ T = T_{n} - ( T_{n} - T ) \in B(X,Y) $$

Now, considering $\| x \| = 1$, for all $x \in X$, since $\displaystyle {{ \| ( T_{n} - T ) x \| } \over { \| x \| }} < \epsilon$,

$$ \| T_{n} - T \| = \sup\limits_{\substack{x\in X \\ \left\| x \right\|=1 }} {{ \| ( T_{n} - T ) x \| } \over { \| x \| }} < \varepsilon $$

Every Cauchy sequence $\left\{ T_{n} \right\}_{n \in \mathbb{N}} $, when $n \to \infty$, converges to some $T \in B(X,Y)$, so $B(X,Y)$ is complete.

Part 3.

$B(X,Y)$ is a complete normed space, hence a Banach space.

■

Kreyszig. (1989). Introductory Functional Analysis with Applications: p92~97, 118~119. ↩︎