Hahn Banach Theorem for Real, Complex, Seminorm

The Hahn-Banach Theorem for Real Numbers1

Let $X$ be a $\mathbb{R}$-vector space and assume that $Y \subset X$. Let us define $p : X \to \mathbb{ R}$ as a sublinear linear functional of $X$. Now, assume that $y^{\ast} : Y \to \mathbb{ R}$ satisfies the following condition as a $\mathbb{R}$-linear functional of $Y$.

$$ y^{\ast}(y) \le p(y)\quad \forall y\in Y $$

Then, there exists a linear functional $x^{\ast} : X \to \mathbb{R}$ of $X$ that satisfies the following conditions:

(a) $x^{\ast}(y)=y^{\ast}(y),\quad \forall y \in Y$

(b) $x^{\ast}(x) \le p(x),\quad \forall x \in X$

Explanation

To say that $\mathbb{R}-$ is a vector space means it is a vector space over the field $\mathbb{R}$. In other words, it means that the conditions for scalar multiplication of a vector space, $(M1)$~$(M5)$, hold true for real numbers. Similarly, the term $\mathbb{R}$-linear means that the two properties of linearity, specifically scalar multiplication, hold true for real numbers.

Since $X, Y$ is a $\mathbb{R}$-vector space, the terms linear and $\mathbb{R}$-linear mean the same. If this concept is confusing, think of $\mathbb{R}$-, $\mathbb{C}$- as non-existent in this text for ease of understanding the proof. Later, when applying the Hahn-Banach theorem to normed spaces, the function $p$ corresponds to the norm. The proof of the theorem stated above is omitted and will be used as a lemma for proving the Hahn-Banach theorem for complex numbers.

The Hahn-Banach Theorem for Complex Numbers2

Let $X$ be a $\mathbb{C}$-vector space and assume that $Y \subset X$. Let us define $p : X \to \mathbb{ R}$ as the following sublinear functional.

$$ p(\lambda x)=|\lambda| p(x),\quad x\in X, \lambda \in \mathbb{C} $$

And assume that $y^{\ast} : Y \to \mathbb{ C}$ satisfies the following condition as a linear functional of $Y$.

$$ \begin{equation} \text{Re}\left( y^{\ast}(y) \right) \le p(y),\quad \forall y\in Y \end{equation} $$

Then, there exists a linear functional $x^{\ast} : X \to \mathbb{C}$ of $X$ that satisfies the following conditions:

- $x^{\ast}(y)=y^{\ast}(y),\quad \forall y \in Y$

- $\text{Re}(x^{\ast}(x)) \le p(x),\quad \forall x \in X$

Explanation

Compared to the theorem for real numbers, the codomain of $p$ being $\mathbb{R}$ remains unchanged because, as mentioned above, when $X$ is a normed space, $p$ corresponds to the norm. $X$, $Y$ are $\mathbb{C}$-vector spaces and since $\mathbb{R} \subset \mathbb{C}$, they also satisfy the conditions for being a $\mathbb{R}$-vector space. This is because if all conditions for a vector space, $(M1)$~$(M5)$, hold true for all complex numbers, they automatically hold true for all real numbers as well. Similarly, $y^{\ast}$, $x^{\ast}$ being $\mathbb{C}$-linear means they also satisfy the condition of being $\mathbb{R}-$ linear.

Proof

Define the function $\psi : Y \to \mathbb{ R}$ as follows:

$$ \psi (y) = \text{Re} ( y^{\ast}(y) ) $$

Then, it can be shown that $\psi$ is also a $\mathbb{C}$-linear functional of $Y$. This is a trivial result since $\mathrm{ Re}$ and $y^{\ast}$ are linear, and the demonstration is very straightforward, thus omitted. By the definition of $\psi$ and $(1)$, the following equation holds:

$$ \psi(y)= \text{Re} \left( y^{\ast}(y) \right) \le |y^{\ast}(y)| \le p(y) $$

Therefore, by the Hahn-Banach theorem for real numbers, there exists a $\mathbb{R}$-linear functional $\Psi : X \to \mathbb{ R}$ of $X$ that satisfies:

$$ \Psi (y) = \psi (y),\quad \forall y \in Y $$

$$ \Psi (x) \le p(x),\quad \forall x \in X $$

Next, define a new function $\Phi : X \to \mathbb{ C}$ as follows. The final goal is to show that the defined $\Phi$ is the $x^{\ast}$ mentioned in the theorem.

$$ \Phi (x) := \Psi (x) -i \Psi(ix) $$

Then, $\Phi$ can be seen as a linear functional of $X$. Since $\Psi$ is $\mathbb{R}$-linear, linearity with respect to addition and multiplication by real numbers is trivial, so only $\Phi(ix)=i\Phi(x)$ needs to be verified.

$$ \begin{align*} \Phi(ix) =&\ \Psi(ix) -i \Psi( -x) \\ =&\ \Psi(ix)+i\Psi(x) \\ =&\ -i^2 \Psi(ix)+i\Psi(x) \\ =&\ i \big( \Psi(x)-i\Psi(ix) \big) \\ =&\ i\Phi(x) \end{align*} $$

$\Phi$ satisfying (a) can be shown as follows. If we assume $y \in Y$,

$$ \begin{align*} \Phi(y) =&\ \Psi (y) -i \Psi(iy) \\ =&\ \psi(y) -i\psi(iy) \\ =&\ \text{Re} \left( y^{\ast}(y) \right)-i\text{Re} \left( y^{\ast}(iy) \right) \\ =&\ \text{Re} \left( y^{\ast}(y) \right) +\text{Im} \left(-iy^{\ast}(iy) \right) \\ =&\ \text{Re} \left( y^{\ast}(y) \right) +\text{Im} \left( y^{\ast}(y) \right) \\ =&\ y^{\ast}(y) \end{align*} $$

Proving that $\Phi$ satisfies (b) is even simpler.

$$ \mathrm{Re }\left( \Phi(x) \right) = \Psi(x) \le p(x) $$

Therefore, since $\Phi$ is a linear functional of $X$ and satisfies (a), (b), $x^{\ast}=\Phi$ exists.

■

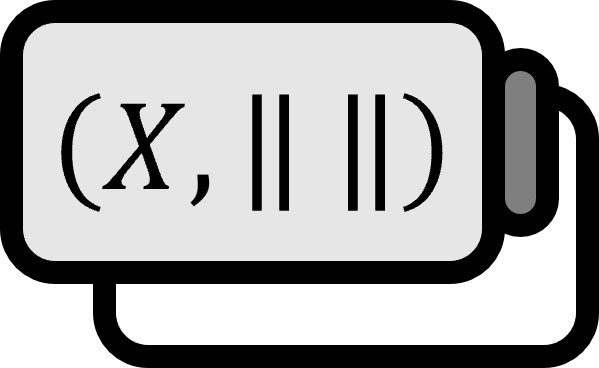

The Hahn-Banach Theorem for Seminorms

Let $X$ be a $\mathbb{C}$-vector space and assume that $Y \subset X$. Let $p : X \to \mathbb{ R}$ be a seminorm of $X$. And assume that $y^{\ast} : Y \to \mathbb{ C}$ satisfies the following condition as a linear functional of $Y$.

$$ | y^{\ast}(y) | \le p(y),\quad \forall y\in Y $$

Then, there exists a linear functional $x^{\ast} : X \to \mathbb{C}$ of $X$ that satisfies the following conditions:

$x^{\ast}(y)=y^{\ast}(y),\quad \forall y \in Y$

$| x^{\ast}(x) | \le p(x),\quad \forall x \in X$

Proof

From the definitions of seminorm and sublinear, if $p$ is a seminorm, it automatically satisfies the conditions of being sublinear.

It is trivial that the following equation is satisfied:

$$ \text{Re} \left( y^{\ast}(y) \right) \le |y^{\ast}(y) | \le p(y) $$

Therefore, by the Hahn-Banach theorem for complex numbers, there exists a linear functional $x^{\ast} : X \to \mathbb{C}$ of $X$ that satisfies the following two conditions:

$$ x^{\ast}(y)=y^{\ast}(y) \quad \forall y \in Y $$

$$ \text{Re} \left( x^{\ast}(x) \right) \le p(x) \quad \forall x \in X $$

Let’s assume $S = \left\{ \lambda \in \mathbb{C} : | \lambda | =1 \right\}$. Then,

$$ \begin{align*} \text{Re} \left( \lambda x^{\ast}(x) \right) =&\ \text{Re} \left( \lambda x^{\ast}(\lambda x) \right) \\ \le & p(\lambda x) \\ =&\ |\lambda| p(x)=p(x) \quad \forall x \in X \end{align*} $$

For a fixed $x \in X$, a $\lambda \in S$ that satisfies $|x^{\ast}(x)|=\lambda x^{\ast}(x)$ can always be found. Thus, for that particular $\lambda$, the following equation holds:

$$ | x^{\ast}(x) | =\lambda x^{\ast}(x) = \text{Re} \left( \lambda x^{\ast}(x) \right) \le p(x), \quad \forall x \in X $$

Since the linear functional $x^{\ast}$ of $X$ satisfies both conditions, the proof is complete.

■

Appendix

For a fixed $x$, let’s say $x^{\ast}(x)=a+ib$. If we assume $\lambda=c+id$, then because of the condition on $\lambda$, $c^2+d^2 =1$, thus $\lambda=c+i\sqrt{1-c^2}$ holds. Also, $|x^{\ast}(x)|=\sqrt{a^2+b^2}$ holds. Considering $\lambda x^{\ast}(x)=(ac-b\sqrt{1-c^2})+i(a\sqrt{1-c^2}+bc)$, and since $|x^{\ast}(x)|$ is a non-negative real number,

$$ \begin{align*} && a\sqrt{1-c^2}+bc =&\ 0 \\ \implies&& a^2(1-c^2) =&\ b^2c^2 \\ \implies&& a^2 =&\ (a^2+b^2)c^2 \\ \implies&& c^2 =&\ \dfrac{a^2}{a^2+b^2} \tag{2} \end{align*} $$

For convenience, let’s denote $c=\dfrac{a}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2}}$. And let’s set $d=\dfrac{-b}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2}}$. Then, $(2)$ and $c^2+d^2=1$ hold true. Also, $|x^{\ast}(x)|=ac-bd=\sqrt{a^2+b^2}$ is true. Therefore, for a fixed $x$, if $x^{\ast}(x)=a+ib$, then for $\lambda=\dfrac{a}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2}}-i\dfrac{b}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2}}\in S$, $|x^{\ast}(x)|=\lambda x^{\ast}(x)$ holds true.